Obed Manuel couldn’t believe what he was seeing, and he had seen a lot, covering the immigration beat for The Dallas Morning News. He’d reported on a protest at Dallas City Hall against the Trump administration’s treatment of asylum seekers; a U.S citizen wrongfully detained by border patrol agents near a checkpoint in the Rio Grande Valley; the fears of the immigrant community resulting in an undercount in the U.S Census. But never had he seen such mass pandemonium as he did on April 3, 2019, when the Immigration and Customs Enforcement agency conducted one of its largest raids of the decade on a North Texas cellphone refurbishing company.

Obed didn’t observe the actual raid, just its aftermath, as the 400 or so people who were arrested earlier in the day were brought to ICE offices in downtown Dallas for processing. A crowd had gathered under grey skies: some were family, some were protesters, others were immigration advocates, separated by a chain-link fence from those arrested and hurried inside.

The protesters were yelling and chanting, holding up signs that read, “No human is illegal,” and “ICE, stop terrorizing our communities.” A man on a megaphone encouraged the chanting, while other activists handed out cookies and snacks. Immigration attorneys gave on-the-spot legal advice to distressed family members worried about their detained relatives. Some of the families were crying, sobbing, while others stood silently waiting to catch a glimpse of their loved ones.

As the hours passed, the number of detainees started whittling from 400 to 280. Even though Obed had not been assigned to the story, he felt obliged to stay, jotting down notes for colleagues at the Morning News, in case they needed him to contribute to their reporting. “If you want photos of the families waiting for their loved ones,” he would tell them. “This is where you need to be.”

Despite the late hour and the chilled air, Obed interviewed several people, sending story feeds to the newspaper. As he prepared to leave, his eyes met those of a teenage boy.

The boy was standing alone, holding a Manila folder in his hand. He was around 15, with brown skin and black hair, and looked like many of the boys with whom Obed had grown up in Dallas. Obed wondered about him: Why was he there? All by himself? Didn’t he have school the next day?

Obed approached him. “Hey, are you with someone? Are you okay?”

The boy replied, “My mom is inside. She’s been arrested.” His younger brother was also home alone.

Obed could have used the boy as a source for his story, gained a human-interest angle, interviewing him about his situation. Would he wake up to an empty house the next morning? Did he have money for breakfast? Would he ever see his mom again?

Instead of being a journalist, Obed put down his reporter’s notebook and reached out to the boy, one immigrant to another, one human to another. “Tell me if they let your mom out,” said Obed, writing down his cell number and handing it to the boy. “Just let me know that you are going to be okay.”

It wasn’t hard for Obed to empathize with the teenager. He understands what it’s like to grow up as an immigrant in America and he brings that sensitivity to his stories. Even though he is still learning—a young reporter on a politically charged beat—he has been developing sources, earning trust, trying to bring some humanity to those whose stories might otherwise go under-reported. With his reporting, he wants others to see his subjects as real people. “If [readers] do not feel that way,” he says, “I have not done my job right.”

His writing gained the attention of Charles Sennott, who hired him as a fellow for his Report for America corps, a nonprofit which sees its mission as saving local reporting from the ground up by working with local media outlets to help train and support the best emerging journalists. “From day one,” says Sennott, the co-founder of the organization, “Obed has been one of the stars of the Report for America program.”

After his long day reporting on the ICE raid, Obed put his story to bed. He returned home, and began to unwind. Around 11:30, his phone sounded with its familiar ping. Only this one made his otherwise serious face light up. It was a text message. It was from the boy. “I got my mom back,” it read. “She is with me now.”

JOURNALISTS ARE BRED TO BE a skeptical bunch, traditionally reporting on the communities they cover without becoming part of them, remaining detached from the people they cover, without becoming attached to them. Not so with Obed Manuel, who has been in love with Dallas, the city he covers, ever since he immigrated there from Monterrey, Mexico as a small boy in 1996.

His parents came to this country like so many of their neighbors in the Oak Cliff section of Dallas: to make a better life for their children. Because they only spoke Spanish, their livelihoods were limited, working at random jobs before they started selling tacos—a lot of tacos – enough to eventually start a catering business. “It’s all about adjusting to a new life in a different place,” Obed says. “The fact that I grew up as an immigrant here in this country gave me an understanding of what that means, at least in the modern context, to be an immigrant in modern America.”

Obed picked up English within six months of his arrival. Attending school with “mostly immigrant kids,” he never experienced discrimination or prejudice – not until his family ventured beyond Oak Cliff when his father, also a minister, would take them on weekends to churches in small Texas towns to preach. On one trip to Mineola, Obed’s family stopped at a gas station. Each of them picked a bag of chips and went to the counter to pay. The woman behind the counter said, “That will be $25.” Even as a child, Obed knew it couldn’t cost that much. His parents told him, “Just drop it. We know what’s happening.” But the encounter made Obed feel different. “When we went to small towns, that’s where we really saw the divide where people looked at us funny for speaking Spanish.”

As Obed grew older, he recognized there were gaps in his knowledge about the culture beyond his neighborhood, gaps he filled by becoming a voracious reader and developing an early passion for writing. “I think for me, that was one of my biggest struggles, learning new things about the local culture and the U.S. almost every day.”

But learn he did, as he attended the University of North Texas’ Mayborn School of Journalism, where he gained valuable reporting experience as a staff writer for the student newspaper, and as an unpaid intern in 2014 at the Dallas Observer, the city’s alternative weekly. Even at the Observer, Obed was drawn to stories about immigration, writing about the wave of unaccompanied minors from Central America who crossed the border, only to be detained by Border Patrol agents. Or later, covering a city council meeting for the small online publication, Latina Lista, when protesters demonstrated against the police shooting of an undocumented immigrant killed during a traffic stop. He would pick up other freelance work, sometimes writing without pay, other times working for $30 a post. “My entry into my career wasn’t forged by my dad or mom,” Obed says. “The only way to do it for me was to work for free and to have my work published without being paid for it.”

The experience helped him overcome the awkwardness many young reporters face when approaching sources cold. “I had just finished college, and I wasn’t the best reporter,” he admits. “Back then, I was afraid to go up to people and talk to them. Now, I really don’t have that problem.”

It also groomed him for his first paying job. He became associate editor at Central Track, a Dallas-based online publication, known for its trendy, sometimes biting arts and entertainment coverage. Although its pages identified Obed as “a taco lover, soccer aficionado and an occasional jogger,” he also focused on “city news, politics and social change movements.”

Although he enjoyed his time at Central Track, he began to doubt whether he would succeed in journalism and considered other career options. But in the summer of 2018, a reporter from The Dallas Morning News told Obed about an opening with Report for America. The program saw its mission as saving local journalism by placing emerging journalists in local newsrooms across the country to report on under-covered issues and communities. And the Morning News had just become one of the local newsrooms that would be participating in the program.

Obed wasted little time in applying. From the time he was a young boy in Oak Cliff, his dream was to write for The Dallas Morning News. And how great to write about the city that he loved, the place that offered refuge to his parents and his grandparents. The job description said “reporting on second generation Hispanic immigrants.” He had focused most of his short career on Latino issues in Dallas. “And I was like, if I don’t get this, then I’ve been doing my job all wrong.”

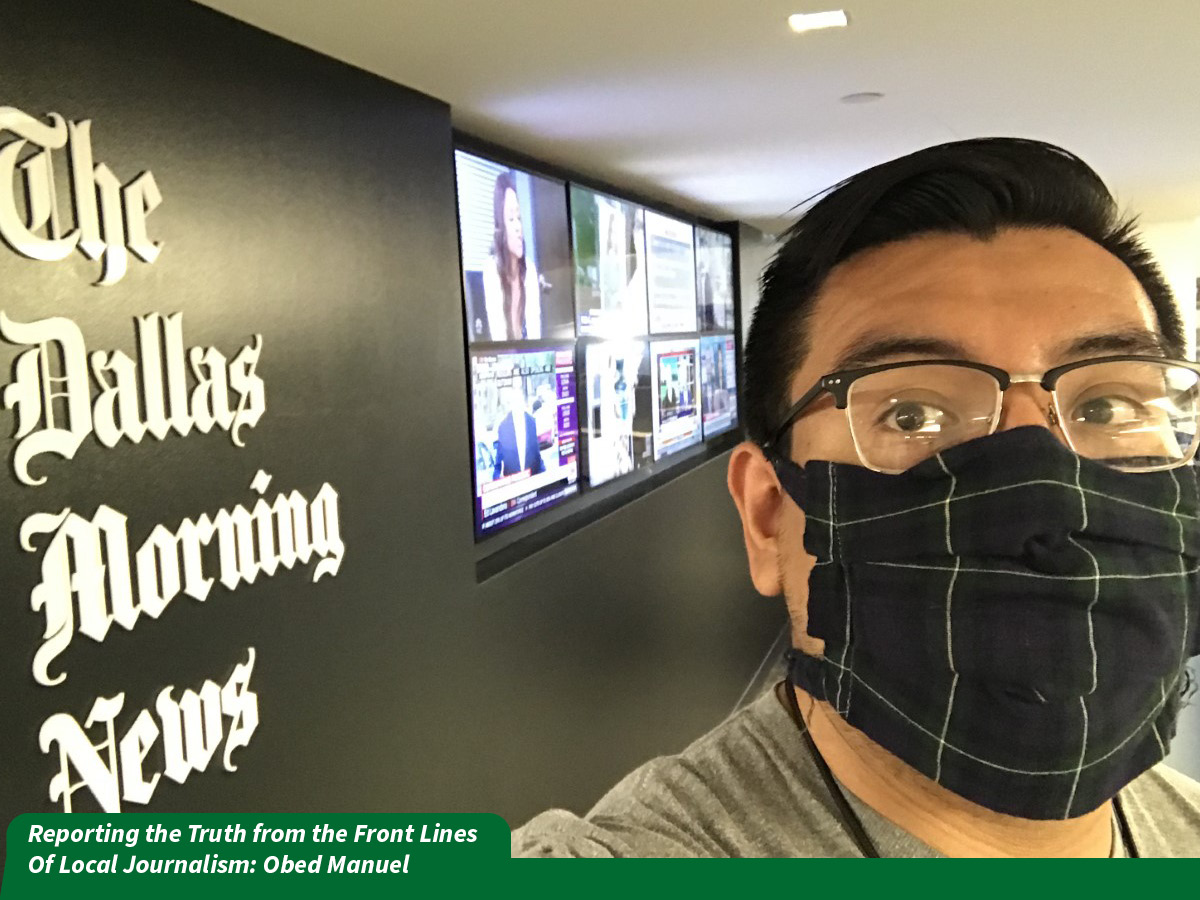

But he did get the job—one of 10 Report for America fellows selected in the program’s second year. He started in August 2018, his salary split between Report for America, donors and the Morning News. “I get to write for my hometown newspaper and they trust me to publish my work,” he says. “That’s about the best reward I could have asked for.”

IT WASN’T AS THOUGH OBED was parachuting into a new beat, starting from scratch, cultivating sources, trying to learn who held the power in the city and who abused it. Dallas had always inspired him and Oak Cliff was where he grew up. His familiarity with its immigrant community helped him overcome that community’s natural reluctance to trust the press and brought a special skill to his reporting.

In an Oct. 11, 2018, essay that he wrote for Report For America, Obed encouraged journalists to reach out to marginalized communities to get their stories. “That’s how we can get them engaged with our coverage. But it all starts with the simple effort of talking to them.”

Report for America’s mission of saving local journalism rang louder for Obed since he also felt he was helping his hometown newspaper. Not only was he a journalist embedded in a city, he was also a resident of that city. “I care deeply about what happens here,” he says.

“When the city hurts, we all hurt with it.”

Each day Obed would work his beat, checking in with advocacy organizations, legal clinics, community organizers-- those who worked with vulnerable populations like undocumented immigrants or lowincome families. “I like talking to people – meeting people and earning their trust enough for them to let me tell their stories.”

And the stories would come as he followed the advice of a mentor at a seminar. “He said, ‘it’s the reporting that will guide us.’ I want to get that tattooed on my back.” Are reporters asking the right questions? Should they be asking more questions? “That’s how you get to know your story…So simple, right? So basic.”

Over time, he marked several personal reporting milestones: his first front page story, complete with bright colorful graphics; his first long-form article, which topped 3,000 words; and his first article that employed data to enhance its storytelling.

Despite reaching these goals, Obed says he sees each story as a learning opportunity, a chance for him to hone his craft. For just as his parents wanted to make a better life for their family, he wants to make a better life for his—even though at present that only includes his wife, his cat, and his dog Pebbles who sleeps on a couch close by Obed while he reports from his home during the pandemic. “I have to be a better reporter and writer,” he says. “Every day, I try to become better at those two things.”

The most influential story of his career came in the summer of 2019 when he received a tip from a local community organizer who asked Obed if he knew anything about Francisco Galicia, a U.S. citizen who had been detained in ICE custody in South Texas for three weeks. He was traveling to a soccer match with his younger brother and a friend and was stopped at a border patrol checkpoint. Francisco told the border patrol he was a U.S. citizen but agents did not believe him not even after presenting them with a Texas driver’s license – not even after his attorney later presented agents with a wallet-sized birth certificate reflecting he was born in Dallas. The agents thought the documents were fake, their belief bolstered by the other two occupants of the car who were unauthorized. His brother self-deported and Francisco was taken to a detention facility.

When Obed got the tip, he couldn’t imagine the story hadn’t been heavily covered. But after a quick Google search, he was shocked to learn no media outlet had reported the story. Obed spoke with Francisco’s attorney and his mother who seemed desperate for someone to listen. They provided Obed with documents that proved Francisco’s citizenship.

Within hours of Obed breaking the story on July 22, it went viral. CNN, CBS, and many other national news platforms picked up the story. Obed even appeared on CNN to explain what had happened. The next day, Francisco was released. In his first words to his mother, Francisco told her by phone, “Mommy, they let me go. I am free now.”

After the release, Obed traveled to the Rio Grande Valley to interview Francisco who told him about the harsh conditions in which he had been held for 23 days: 60 men, many of them sick, crammed into a cell that was built to hold people for three days; no showers, no beds, poor food.

“You know you take that home with you as a reporter,” Obed said in a Dallas Morning News video about the story. “You can’t unlearn these things —you just can’t.”

Within days of the article’s publication, the story was discussed during a congressional hearing. “That was definitely the most successful professional week that I have had,” Obed says.

He had validated the mantra of Report for America by listening to the members of an under-covered community when no other journalists seemed interested in listening. He had given voice to people who might otherwise be voiceless. And his story had made a difference in the lives of the people it touched, likely attracting more minority readers by showing them that local journalism matters.

“There are reporters of color out there who want to bring more people into the conversation,” Obed says. “The truths that are out there, need to be told. I think it’s our time to tell our stories.”