Maybe you were there and can recall what he said, or maybe you heard about it from someone who was there. But when two-time Pulitzer Prize winning feature writer Gene Weingarten decided to host a Q&A session at the 2011 Mayborn Literary Nonfiction Conference, what he said polarized the audience and sent Twitter a-trending. Whether it was some kind of narrative mea culpa for past reporting indiscretions or a chance to educate emerging journalists about the ethical traps the pursuit of truth places in the path of every good reporter, Weingarten expressed little regret about the two scenarios he mentioned.

“I was very comfortable with the way I acted in those situations, except one,” Weingarten would later say.

The first situation dealt with a 2004 story published in The Washington Post, where he was on staff until his retirement in 2009. He continues to write “Below the Beltway,” a syndicated humor column for the newspaper. But the story he mentioned at the conference concerned a pressing question in the run-up to the 2004 presidential election: Why were so many Americans not voting? To answer that question, Weingarten spent several days with a non-voter in rural Michigan. But even though he did his best to immerse himself in the man’s life, he was having trouble getting the man to open up to him. And while Weingarten and his subject liked each other, the man didn’t seem to trust him.

After two days, Weingarten felt the article was falling flat, but things changed on the third day. Weingarten went to the man’s house for a barbecue and a friend of the man pulled out a marijuana pipe which he offered to Weingarten. The conflict seemed obvious: The Washington Post had a strict policy that its journalists could not break the law while reporting a story, and in Michigan at that time, possession of marijuana was against the law. On the other hand, “I felt if I had a chance at the kind of intimacy I wanted in this interview, it was now or never.”

Weingarten chose the pipe and the pot. With this truth revealed, he asked the Mayborn crowd if they would do the same. As he recalls, one-third of the audience raised their hand for ‘yes” and two-thirds said “no.” While the ethical lines seemed clear, Weingarten felt that he hadn’t done anything wrong. He understood he had a duty to represent The Washington Post as it would like to be represented, but he also knew his journalistic duty was to get the story.

“The story went from a B minus to an A,” Weingarten said. “I don’t regret it. I don’t apologize for it.”

Weingarten did express some regret to the audience about a second incident, one that transpired early in his career when he was a young reporter for The Knickerbocker News in Albany, New York. The city of Albany was engulfed in a bribery scandal, and a businessman at the center of the scandal had been hospitalized.

Weingarten snuck into the man’s hospital room. “He was in and out of lucidity,” Weingarten said. “He addressed me as ‘doctor,’ even though I told him I was a journalist. I again told him I was a journalist, and he seemed to understand that, but instead of shaking his hand, I took his pulse.” From the information the man gave him that day, Weingarten broke the story and landed on the front page.

“I would never do it again,” he said. “I think it was the only dishonest thing I did as a journalist.”

A writer from the Washingtonian magazine was in the audience at the conference, shadowing him for an extensive profile that he would publish about Weingarten five months later. In his profile entitled “How Do You Explain Gene Weingarten?” Tom Bartlett was troubled about why Weingarten would sully his own reputation. “My theory is that this is consistent with his tendency toward self-flagellation,” wrote Bartlett. “He reveals his faults in his columns. He writes stories about people whose mistakes and quirks mirror his own.”

Although Weingarten would disagree with this “theory,” Bartlett did have a point.

Take his gut-wrenching Pulitzer Prize winning story, “Fatal Distraction,” about parents who carelessly, unwittingly leave their young children in the backseat of their cars to die from hyperthermia. Weingarten told NPR that he had his own moment 30 years before when he “came within seconds of killing” his daughter. “The only reason that she’s alive today is that at the last minute, just before I was about to turn off the car and go into work in a 90-degree Miami day, she woke up and said something. And that’s why she’s alive and not a little pile of bones in the ground somewhere…I tell you this can happen to anyone.”

Weingarten also identified with the central character of what many believe is his best narrative work, “The Peekaboo Paradox,” about children’s performer, Eric Knaus, who went by the stage name of “The Great Zucchini.” Eric had an innate sense of playfulness and foolish wonder that made young children melt with laughter. But as Weingarten artfully peels back the onion of Knaus’ adult life, he reveals The Great Zucchini to be a certifiable mess. Weingarten, never one to shy from confession, writes in the piece: “I’ve known other men who approach Eric’s level of dysfunction, including myself.”

For Weingarten, being unapologetically himself and maintaining his journalistic integrity are not mutually exclusive. And as a humor writer, he finds himself to be the best butt of every joke. “Selfdeprecating humor is something everyone likes, and it keeps you in your place,” he says. “I like confessing to my foibles – you can’t get too full of yourself if half of what you write is making fun of yourself.”

Inspiration for his narratives not only stems from his own quirks, neuroses and eccentricities, but also from his insight about the fundamental nature of storytelling. He has dedicated much of his journalism to the notion that “there is a story in everything”; that no matter how mundane, trivial or boring something might seem, if you dig deep enough, searched for the truth hard enough, you could find the extraordinary in the ordinary. His latest book seems an attempt to actually prove this philosophy.

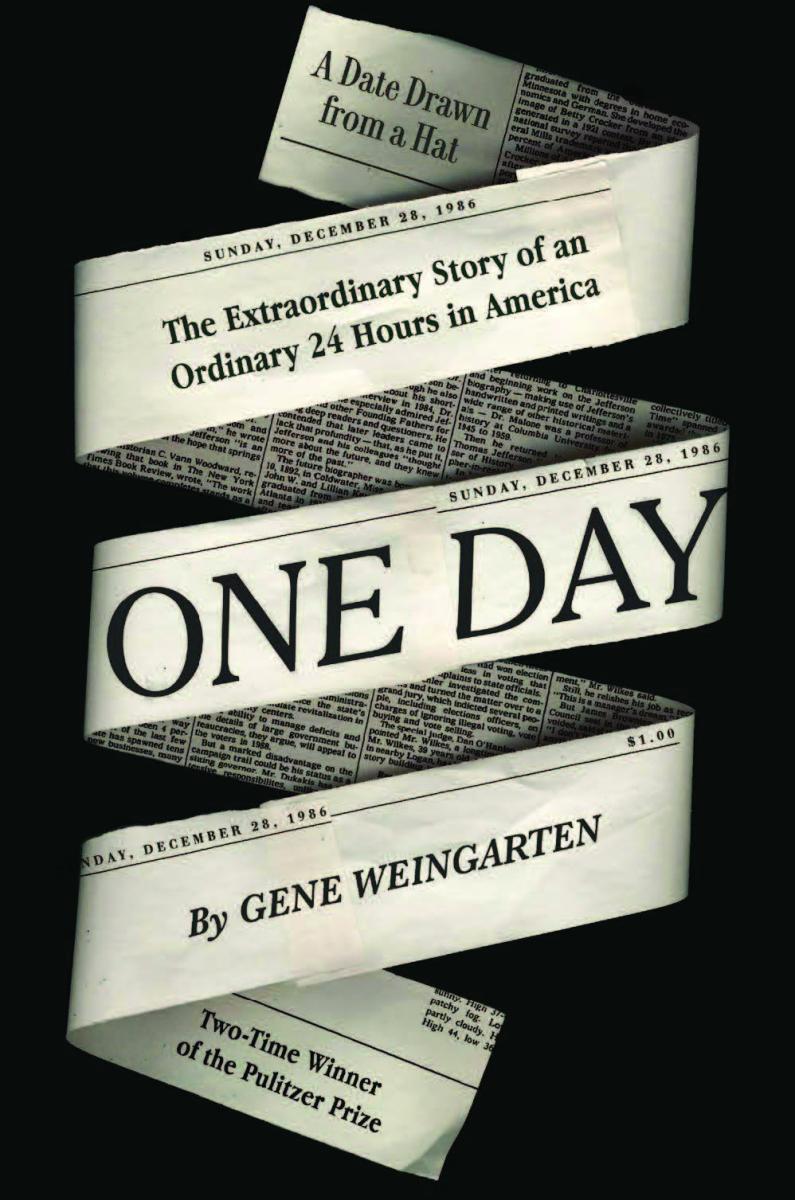

“One Day: The Extraordinary Story of an Ordinary 24 Hours in America,” released in 2019, is the compilation of six years of interviews that examines the title’s implicit premise: there is no such thing as an ordinary day. His methodology for picking that single day drew media attention to the book.

“I went to a restaurant, brought [an] old green fedora,” he told NPR in an interview. Inside were 63 crumpled pieces of paper — 31 on the first drawing, drawn by a little boy for the day of the year. Twelve in the second one for the month the year, and 20 for the third one; I had limited the year to one of 20 years. I wanted people alive who I could talk to who remembered what happened. So, we limited it to 1969 to 1989.”

The date chosen was December 28, 1986 — which, in the hands of a lesser writer, might have dampened interest. December 28 was a Sunday, a slow news day during a slow news cycle – the holidays between Christmas and New Year’s.

But Weingarten found much to write about: a heart transplant, a fire fighter, a romance, a chapter on AIDS, which was still raging at the time. And if the book review in The Washington Post was any indication, Weingarten had proven his point:

“‘One Day’ is full of scenes and wordsmithing that can make a reader elbow her partner in the ribs and force him to listen to a read-aloud. That’s the hallmark of memorable feature writing. More, please.”